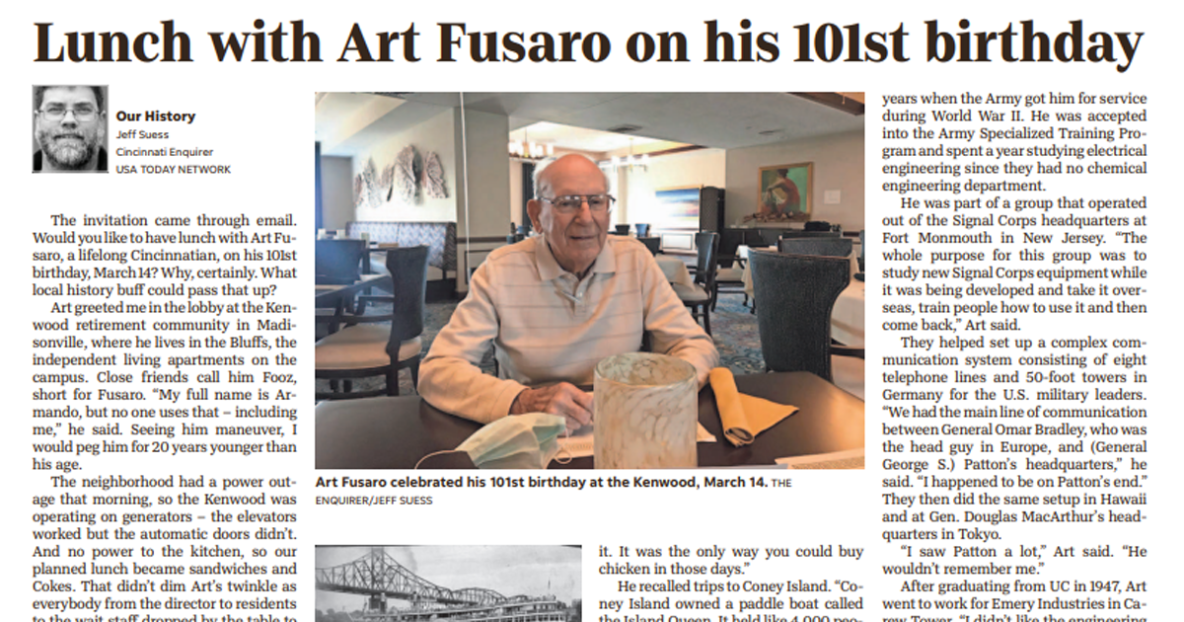

The invitation came through email. Would you like to have lunch with Art Fusaro, a lifelong Cincinnatian, on his 101st birthday, March 14? Why, certainly. What local history buff could pass that up?

Art greeted me in the lobby at the Kenwood retirement community in Madisonville, where he lives in the Bluffs, the independent living apartments on the campus. Close friends call him Fooz, short for Fusaro. “My full name is Armando, but no one uses that – including me,” he said. Seeing him maneuver, I would peg him for 20 years younger than his age.

The neighborhood had a power outage that morning, so the Kenwood was operating on generators – the elevators worked but the automatic doors didn’t. And no power to the kitchen, so our planned lunch became sandwiches and Cokes. That didn’t dim Art’s twinkle as everybody from the director to residents to the wait staff dropped by the table to wish him a happy birthday. “You look damn good to be 101,” the waitress said. “You could live to be 121.”

Secret to a long life

“The first thing they always ask me is, ‘What do you attribute your long life to?’” Art said. “And I tell them, Mother and Dad came from Italy and it seems like all those people in the Mediterranean live a long time. I think it’s because of diet more than anything, so I figured it might be olive oil.

“So every night before bed, I’d drink a half cup of olive oil,” he said, winding me up, “but I had to quit because I kept sliding out of bed.” Rimshot! “So that’s my answer. Everybody asks me. I’ve just been lucky is all.”

A sense of humor might help. He also mentioned good wine.

Art has lived on his own since his wife Evelyn died in 2020. He cooks his own meals (mostly Italian, but also a mean cheesecake) and still drives a car. He recently had to drive his son to a doctor’s appointment. He exercises at the gym facilities at 7:30 every other morning.

How did they cope with the pandemic?

“We did our own cooking so we weren’t as affected by COVID,” he said. “Over at the apartment, we could come to the functions in here. We got along. … We had a few cases in the beginning, but everybody got the shots.”

Art is a regular at social events at the Kenwood and raves about the presentations by local historian Diane Shields. “She speaks for an hour, no notes. It’s one of the biggest draws we have here,” he said.

He could do a fair share of talking history himself. He has lived a century of everyday experiences in Cincinnati that are what many of us regard as history.

Everyday memories of Cincinnati

Art was born March 14, 1921, and grew up in Hyde Park. I mentioned I was working on a story about Findlay Market, and he had his own memories.

“When I was a kid … every Saturday, my mom and I would walk to Madison Road and get on a streetcar, go Downtown and transfer to another streetcar and go to Findlay Market,” he said. “And every Saturday, we’d come back with two shopping bags full of food, one would always have two live chickens in it. It was the only way you could buy chicken in those days.”

He recalled trips to Coney Island. “Coney Island owned a paddle boat called the Island Queen. It held like 4,000 people. It was what they called a side-wheeler with paddles on the side instead of what they called a stern-wheeler. But they operated from Downtown – Public Landing – and it’d take about an hour to get up there and they had entertainment on the boat. It was really neat. There wasn’t any charge to it. You’d go into Coney Island park and that didn’t have any charge to it.

“It was really a neat amusement park because they kept it so clean. They’d take an hour and go up there and we’d spend all day in the amusement park and Mom would always cook up fried chicken and we’d eat up there.” The Island Queen was destroyed in a fire in 1947.

Art played violin at Withrow High School “a long time ago,” and in the band directed by Smittie. “Did you ever hear of him?” he asked. “He was pretty well known around here.”

That was George G. Smith, known as Smittie, who directed the Withrow Minstrels, a popular variety show that showcased the band as well as soloists and dancers in Broadway-style performances that ran for 35 years (1931-1965).

“That was fun because it was a variety show with all the singers and the dancers and all that kind of stuff,” Art said.

Communication lines in WWII

Art studied chemical engineering at the University of Cincinnati for three years when the Army got him for service during World War II. He was accepted into the Army Specialized Training Program and spent a year studying electrical engineering since they had no chemical engineering department.

He was part of a group that operated out of the Signal Corps headquarters at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey. “The whole purpose for this group was to study new Signal Corps equipment while it was being developed and take it overseas, train people how to use it and then come back,” Art said.

They helped set up a complex communication system consisting of eight telephone lines and 50-foot towers in Germany for the U.S. military leaders. “We had the main line of communication between General Omar Bradley, who was the head guy in Europe, and (General George S.) Patton’s headquarters,” he said. “I happened to be on Patton’s end.” They then did the same setup in Hawaii and at Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters in Tokyo.

“I saw Patton a lot,” Art said. “He wouldn’t remember me.”

After graduating from UC in 1947, Art went to work for Emery Industries in Carew Tower. “I didn’t like the engineering aspect anymore so I eventually ended up as director of advertising.” He worked for the company until he retired in 1986. Retired for 36 years and counting.

One more story

It was time for the cake. The Kenwood staff handed out slices to everyone in the restaurant and we all sang happy birthday. The “101” candles were not lit – you might need special permission from the fire department for that. A resident commented loudly, “Can you imagine living to be 101?”

One more story while we ate dessert.

During a trip to New York, the train stopped at the Norwood station and a limousine pulled up. Emery Industries president John J. Emery, who also built Carew Tower and the Terrace Plaza Hotel, got out of the car with his wife to board the train. Emery saw Art and called out, “Hey, Fooz! Come join me in my cabin for a martini.” Art did and found Emery with a thermos jug of martinis and a basket of fried chicken.

“He loved martinis,” Art said. “Every company party, they’d have double martini glasses ready just in case Mr. Emery showed up.

” Everyone has a story. It’s history, and it’s a worthwhile endeavor to share about the everyday moments of our lives. And someday, we can invite someone to lunch on our birthday for a conversation.